Each year for the past few years, I’ve hoped to return to my pre-pandemic reading levels. It hasn’t happened this year, and it’s probably time to accept I’m unlikely to do so any time soon. There are many factors, but one contributor is simply that I’m reading substantially more non-fiction for research, and I read non-fiction much slower. And that’s okay – it will encourage me to choose my fiction with even more care. So on that front, here are the books that have stayed with me from this year:

Light Perpetual – Francis Spufford (2021)

In one of the most outstanding opening sequences I’ve ever read, a bomb detonates during the second world war in a fictional south London borough, instantaneously wiping out a classroom of children. The novel goes on to extrapolate what the lives of five of these children would have looked like, straddling decades of social and political change with flawless prose and deep humanity.

How High We Go In The Dark – Sequoia Nagamatsu (2022)

Nagamatsu’s novel opens with a Siberian plague, and the proximity of its publication date to Covid-19 inevitably placed it in the ‘pandemic novel’ category. However the novel’s remit is much broader, exploring the attitudes, behaviours and rituals around how we approach and deal with death, as individuals and as societies. From euthanasia theme parks to talking pigs, it’s a whirlwind of imagination and I love the confidence which with these scenarios are presented, without over-explanation, simply asking the reader to go with it and enjoy the ride.

Best of Friends – Kamila Shamsie (2022)

Kamila Shamsie has always stood out for me as a writer who is exceptionally good with character, and her most recent novel is no exception. We meet Zahra and Maryam as teenagers in Karachi, where they experience an incident which will haunt them for decades to come – as they move to London and as their lives, values and careers move further apart. An intimate exploration of friendship over time, as well as an unflinching examination of the darker side of UK politics.

Lamb – Matt Hill (2023)

Similarly unflinching in its portrayal of austerity Britain is Matt Hill’s Lamb. Suffused with eerie descriptions and surreal imagery, Lamb sits closer to the horror end of the science fiction spectrum than I usually read, but Hill’s superb writing and immersive world-building held me spellbound throughout. The novel has the relationship between parents and children very much at its heart – examining the ties that hold us together and the sometimes brutal cost of that love. This book will stick with you.

The Belladonna Invitation – Rose Biggin (2023)

Rose Biggin’s marvellous depiction of fin de siècle Paris is packed with theatrical audacity and lush description. Revolving around a notorious poison salon, the novel follows the dynamic between two women, mysterious to each other and to the reader, in a subversive exploration of power, ambition and desire. Belladonna is a glorious read that leaves you wondering how much you can ever really know someone.

Shark Heart – Emily Habeck (2023)

A few weeks after young lovers Wren and Lewis marry, Lewis receives a terminal diagnosis – his memories and consciousness will remain (mostly) intact, but he will transform slowly into the body of a great white shark. This was another speculative read where I hugely admired the confidence and deceptive simplicity with which this scenario is presented to the reader. Also setting it apart, and with a wonderfully deft touch, was the use of theatre script to tell some sections of the story (as befits Lewis’s background as an actor). A beautiful and wonderfully unexpected read that might just break your heart.

In Ascension – Martin MacInnes (2023)

My year’s reading was bookended by two novels set in space and with common themes, one long and the other short. I read In Ascension whilst on holiday and am very glad I did as it is a novel that demands and perhaps requires full immersion. Told primarily through the perspective of biologist Leigh, who has always been drawn to the ocean, the novel takes the reader from the deepest ocean vents to distant space and the possibility of first contact, in a profound and moving exploration of the connectivity of all living things and the fragility of the one planet we call home. An extraordinary book.

Orbital – Samantha Harvey (2023)

The book I was most looking forward to this year, and it did not disappoint. I’ve loved Samantha Harvey’s writing ever since discovering Dear Thief. This slim volume, tracking 24 hours in the company of six astronauts on the international space station, contains worlds within its exquisitely crafted, beautiful prose. Seen from above, there are no borders on planet Earth, but look long enough and the cracks begin to show. As with In Ascension, this is a novel that pays homage to the beauty of our planet whilst exposing its fragility and the toll of human dominance.

An Immense World – Ed Yong (2022)

An Immense World explores the extraordinary diversity and complexity of the sensory world as experienced by a selection of non-human animals. I read this book slowly, over several months, for research, but I wanted to include it here as the contents are so transformative in how we perceive the world, how we might begin to rethink our commonalities and differences with other beings, how we relate to those we share the planet with, what we are still to understand and what we can never truly know. A genuinely awe-inspiring read.

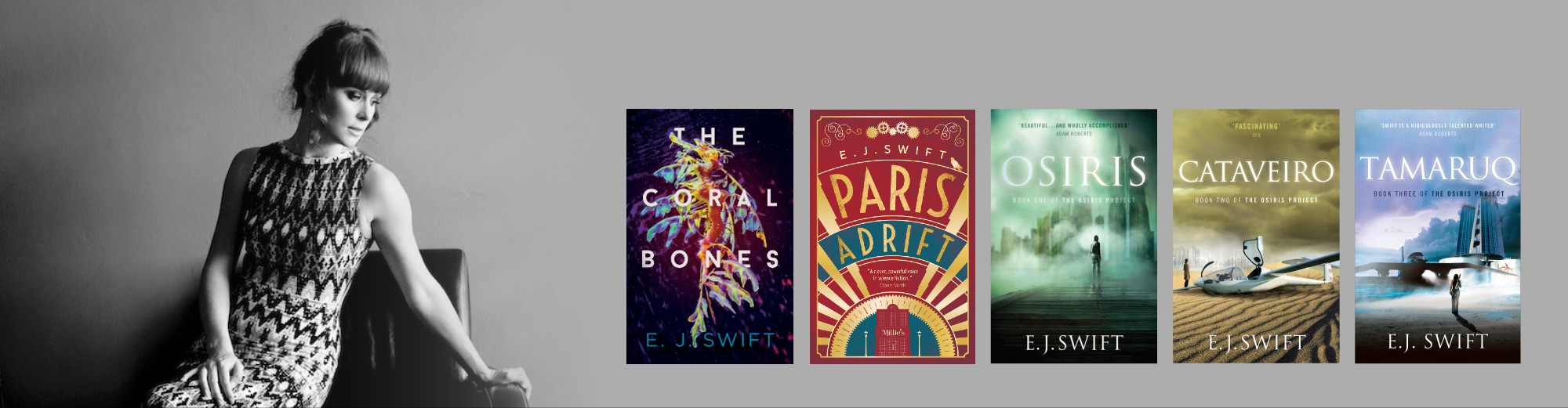

On the writing front, it has been a big year for me. The Coral Bones was shortlisted for the BSFA Award for Best Novel, the Kitschies Red Tentacle for Best Novel, and the Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction book of the year. Amidst this wonderful news, my brilliant publisher Unsung Stories announced they would be closing down. I’ve been very lucky to find a new home for The Coral Bones with Jo Fletcher Books – the ebook is available now and the paperback edition from 4 January. I’m now halfway through a first draft of my new novel, The End Where We Begin, and the first half of 2024 will be very much focussed on finishing this draft.

A huge thank you to everyone who has supported The Coral Bones this year. I can’t say how much it means. And whatever you are reading or writing in 2024, I hope the words bring you inspiration, solace and joy.

Unsheltered – Barbara Kingsolver

Unsheltered – Barbara Kingsolver The World Without Us – Mireille Juchau

The World Without Us – Mireille Juchau Zero Bomb – M. T. Hill

Zero Bomb – M. T. Hill 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World – Elif Shafak

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World – Elif Shafak Wilding – Isabella Tree

Wilding – Isabella Tree Chernobyl Prayer – Svetlana Alexievich

Chernobyl Prayer – Svetlana Alexievich The Heavens – Sandra Newman

The Heavens – Sandra Newman Do You Dream of Terra-Two? – Temi Oh

Do You Dream of Terra-Two? – Temi Oh The Wych Elm – Tana French

The Wych Elm – Tana French Bridge 108 – Anne Charnock

Bridge 108 – Anne Charnock Reservoir 13 – Jon McGregor

Reservoir 13 – Jon McGregor Happiness – Aminatta Forna

Happiness – Aminatta Forna Home Fire – Kamila Shamsie

Home Fire – Kamila Shamsie Fever – Deon Meyer

Fever – Deon Meyer Rosewater – Tade Thompson

Rosewater – Tade Thompson Gnomon – Nick Harkaway

Gnomon – Nick Harkaway Conversations with Friends – Sally Rooney

Conversations with Friends – Sally Rooney When I Hit You – Meena Kandasamy

When I Hit You – Meena Kandasamy Convenience Store Woman – Sayaka Murata

Convenience Store Woman – Sayaka Murata Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories – Vandana Singh

Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories – Vandana Singh Flight Behaviour – Barbara Kingsolver

Flight Behaviour – Barbara Kingsolver Washington Black – Esi Edugyan

Washington Black – Esi Edugyan The Natural Way of Things – Charlotte Wood

The Natural Way of Things – Charlotte Wood The Swan Book – Alexis Wright

The Swan Book – Alexis Wright Speak Gigantular – Irenosen Okojie

Speak Gigantular – Irenosen Okojie The Queue – Basma Abdel Azim

The Queue – Basma Abdel Azim Exit West – Mohsin Hamid

Exit West – Mohsin Hamid Stories of Your Life and Others – Ted Chiang

Stories of Your Life and Others – Ted Chiang Open City – Teju Cole

Open City – Teju Cole You Will Know Me – Megan Abbott

You Will Know Me – Megan Abbott Annihilation – Jeff Vandermeer

Annihilation – Jeff Vandermeer The Forty Rules of Love – Elif Shafak

The Forty Rules of Love – Elif Shafak The Sixth Extinction – Elizabeth Kolbert

The Sixth Extinction – Elizabeth Kolbert Sapiens / Homo Deus – Yuval Noah Harari

Sapiens / Homo Deus – Yuval Noah Harari

Speak by Louisa Hall (Orbit, 2015)

Speak by Louisa Hall (Orbit, 2015) The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall (Faber and Faber, 2015)

The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall (Faber and Faber, 2015) The House of Journalists by Tim Finch (Jonathan Cape, 2013)

The House of Journalists by Tim Finch (Jonathan Cape, 2013) The Boat by Nam Le (Canongate, 2009)

The Boat by Nam Le (Canongate, 2009) Central Station by Lavie Tidhar (Tachyon, 2016)

Central Station by Lavie Tidhar (Tachyon, 2016) Dear Thief by Samantha Harvey (Vintage, 2014)

Dear Thief by Samantha Harvey (Vintage, 2014) The Thing Itself by Adam Roberts (Gollancz, 2015)

The Thing Itself by Adam Roberts (Gollancz, 2015) Dreams Before The Start of Time by Anne Charnock (47 North, 2017)

Dreams Before The Start of Time by Anne Charnock (47 North, 2017)